PC Gaming’s biggest sale is still its best, but it’s losing its charm.

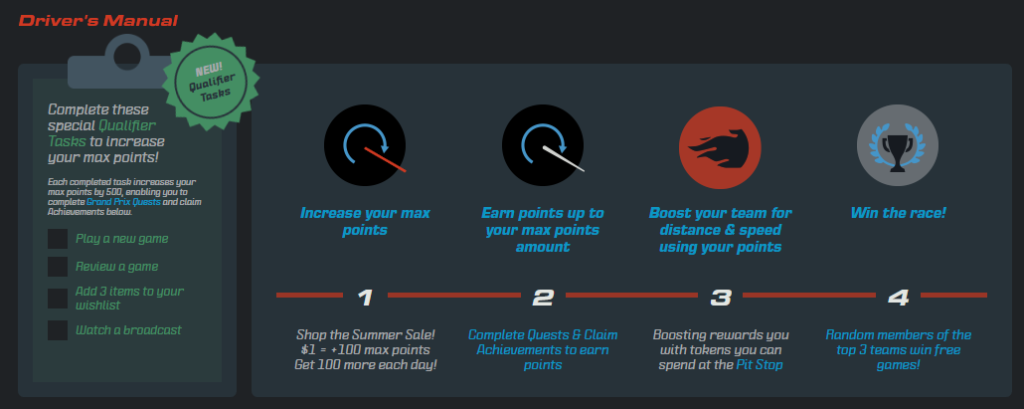

This year’s Steam Summer Sale started earlier this week, ushering in discounts on most titles across the PC gaming storefront. Accompanying this year’s sale is the Steam Grand Prix event, which is… confusing at best, something Valve’s since admitted, and they’ve changed the rules and directions slightly since the initial launch. Still, with the event ‘fixed’ and the sale fully up and running, it’s worth asking: Are Steam Sales fun anymore?

The first sale I participated in was 2011’s Holiday Sale, which offered the deep discounts we’ve come to love, but also the engaging “Great Gift Pile” meta-event. Each day, alongside new deals, players could find and complete new achievements to earn holiday coal, a currency that could be traded in for a guaranteed game, or saved up and put toward a set of drawings held at the end of the event. The Great Gift Pile had its issues, some of which I’ll get into later in this piece. Still, the event made the sale more than a chance to buy cheap games. It was fun.

It’s not a new opinion that the sales of today have declined in quality from those of years past, and it’s hardly controversial to argue that the experience of a Steam Sale has dulled over the past few years. Despite a pretty clear agreement that the sales aren’t what they were, though, there’s some significant disagreement regarding why.

One of the most common arguments online is that the departure of well-known flash sales precipitated the downfall of later sales. Flash sales were short-lived deeper discounts on a limited number of titles. A flash sale would normally last for about eight hours and represent the lowest price a game would be offered at for the duration of the sale. Games that were offered on flash sales would sometimes be offered for the same price during a daily deal, but if not, that short, easily missable eight hour window would have been your last chance for the steeper discount. The flash sales (and daily deals) died in 2015 when Steam introduced its refund system. Now that players could buy and refund any game they’d played for less than two hours, the incentive to wait for a flash sale disappeared. You could easily buy each game you wanted on day one and ask for a refund if the title dropped any lower. The day of the flash sale was gone, but that isn’t what killed the sales at large.

Another argument targets the events built around the 2011 sales, particularly the Holiday Coal meta-game of the 2011-2012 Holiday Sale. Players could complete new, daily in-game achievements and tasks for coal, and later exchange that coal for a guaranteed free game. The event incentivized the playing (and buying) of real games, and the reward for doing so was something players wanted. It was a great event, swiftly ruined by exploits. Spoofing achievements was quicker and easier than earning them, and when done en-masse, it allowed a few unscrupulous system-gamers to reap the bulk of the sale’s rewards before anyone else had a chance to play. A great sale, but a hard one to mimic successfully.

But a successful sale today doesn’t have to be the successful sales of yesterday; it doesn’t even have to emulate them. Valve has at its disposal all of the necessary resources and freedom to craft a fun sale. It’s not the past that’s stopping them, but the money.

This is where most arguments on the subject stop, giving way instead to armchair economists invigorated by the opportunity to explain that Valve is a business, and therefore, its team interested in and primarily motivated by making money. It’s a fair point, but it’s an over-simplification of the situation, because generating income wasn’t always the point of the sale.

When Steam first launched fifteen years ago, the goal of creating a PC gaming storefront with a loyal community rivaling those claimed by the giants of the console world looked like an unrealistic feat. Valve’s goal wasn’t just to sell games, but to become the place consumers went for PC gaming, and to expand the PC audience in doing so. The successful sales of yesterday came as a result of Valve trying their hardest to build this new community and publishers’ willingness to invest in a new(ish) platform, one where games had recently been selling the least.

It’s not Valve’s failure or laziness that brought us to the point we’re at with the sales, but their success. PC gaming is big now, and, despite recent competition from newer storefronts, Steam is where most of it happens. One of the primary reasons recent sales have been worse is that they don’t have to be better. Having accomplished their goals, Valve doesn’t have to work as hard to cultivate an audience of consumers, and with PC gaming back on its feet, publishers don’t have to offer steep discounts to sell their games on the platform.

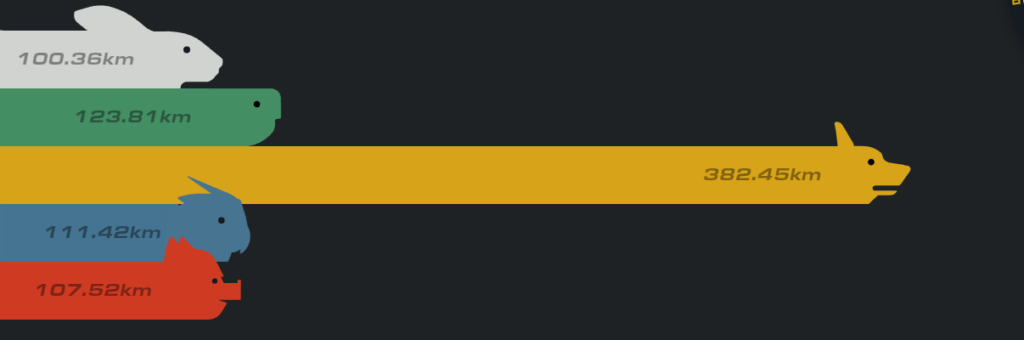

Still, even with less motivation to create impressive sale events, the Holiday and Summer sales continue to take place every year, and with each comes a unique mini-game or event. Sometimes they’re a chance for Valve to put forward interesting artwork, or a neat little mini-game, but they’re never really fun anymore. Now, it’s fair to call that out as subjective, but I don’t think I’m in the minority here. Indeed, looking at recent events, it doesn’t even seem like they’re designed to be particularly fun. Players are either assigned randomly to teams they have no way to properly communicate or strategize with, given the freedom to select the team that everyone else did, or allowed to work together, but at such a scale that close, dedicated teamwork doesn’t really matter at all. These are “community” events in that they require action from a large number of people, but there’s no necessity of interaction between players, no real way to strategize, no game to play.

As the meta-events surrounding the sales continue to stagnate, one element continues to be emphasized: urging players to spend more money. For most of the recent sales, Valve’s used Steam’s trading card system to incentivize more active spending; the more you buy, the more cards you get. Depending on how you view the trading card system, more cards either means more levels on your Steam account or a few extra cents in your wallet. This year, the sale upped the benefit of spending more directly: for every dollar you spend in the storefront, your “maximum boost” for the Grand Prix event is raised by 100 points. The more you spend, the more you can contribute to the game. It’s a direct pay-to-win system.

Now, there’s a decent amount to unpack here. It’s easy to tie this back to the “Valve as a business” argument. Steam is a store, and stores are meant to make money. Steam Sales have always been business endeavors first, but yesterday’s sales went beyond business. The Summer Camp and Holiday Sales of 2011 were fun because of the engaging events that launched beside them. Even today, the existence of the Spring Cleaning event seems to prove that Valve knows the value of just-for-fun community events. Meanwhile, the two most significant sales of the year continue to demonstrate a routine loss of quality.

The Steam Summer and Holiday Sales have always been about selling games, but they’ve also historically been a chance for Valve to create and cultivate experiences for a dedicated community of consumers. Money was always a goal, but so were community engagement and fun. Today, money is the primary, secondary, and tertiary goal of the once-grand Steam Summer Sale, and it’s worse for it.