Looking for the Quick Review?

Viewfinder is a remarkably unique, perspective-challenging puzzle game with a core concept that captivated me and challenged the way I interpreted dimensionality and space. But the first time I came into contact with this title, I couldn’t shake the blurry, stitched-together half-memories of a previous deep dive into the history of F-Stop, the enigmatic, canned first draft of the game that would become Valve’s Portal 2.

Details about F-Stop are scarce beyond the scattered files that remain stuck in the uncleaned niches of Portal 2’s game folders and a since-delisted YouTube video from 2020. By all available internal accounts, the game’s core mechanic was groundbreaking but represented a mechanical separation from the gameplay style and titular portals of its predecessor, a disconnect that confused playtesters. This probably isn’t the only reason F-Stop never saw full production, but further details are trapped beyond Valve’s iron curtain, perhaps never to be explored by those without the necessary handheld portal device and moon rock-coated drywall to bypass its defenses.

What we the laypeople have been able to piece together is that F-Stop replaced its predecessor’s iconic Portal Gun with a specialized camera that allowed players to photograph objects and use the resulting polaroids to duplicate and manipulate them. It’s a really interesting concept, if somewhat difficult to visualize for those who haven’t seen it in action. Still, hearing about it captivated me and, as much as I love the game that eventually replaced it, it irked me that it had never made it out of pre-production. And given Valve’s tendency to shelve projects for good, I assumed the concept might have been lost to history.

Enter Matt Stark. Before I introduce Stark’s project, I should do a little to distance him from my own comparison. Stark’s tweets showing off Viewfinder’s earliest concepts were posted in early 2020, months before the F-Stop footage was shared, and there’s no reason to think he was either directly or indirectly inspired by the Valve project. I’m bringing up the resemblance now because it’ll be relevant later.

Fast forward three and a half years past those first tweets and Matt is now the central figure of Sad Owl Studios, a multi-member company, and Viewfinder is a complete game.

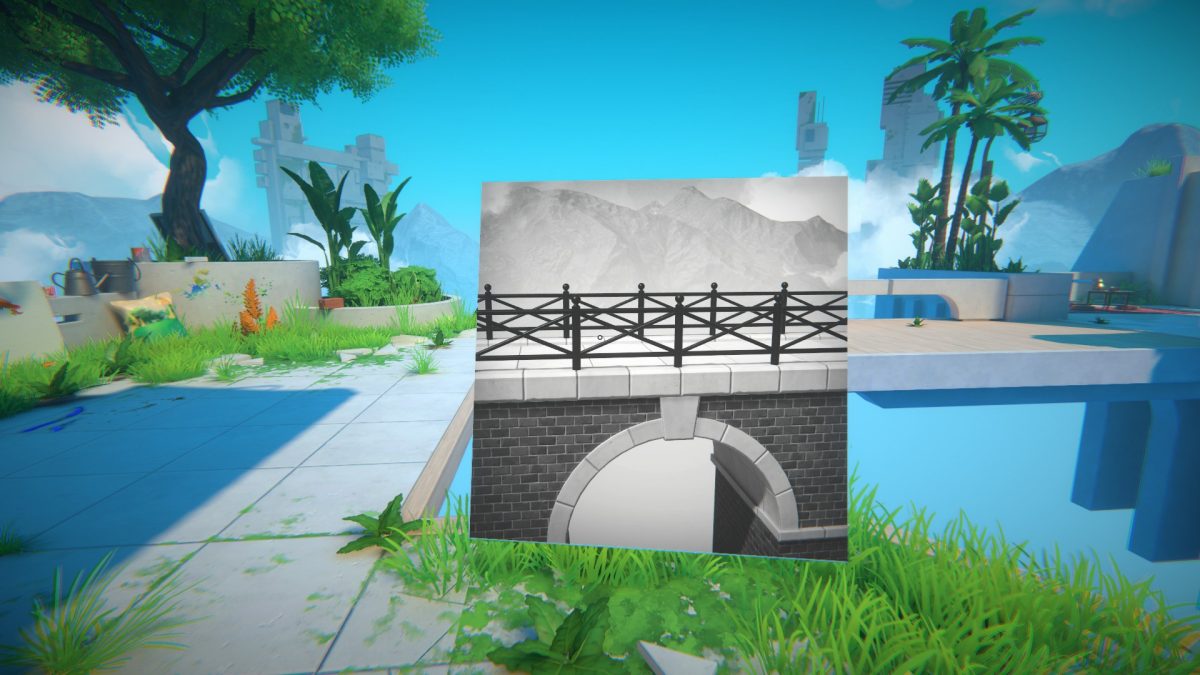

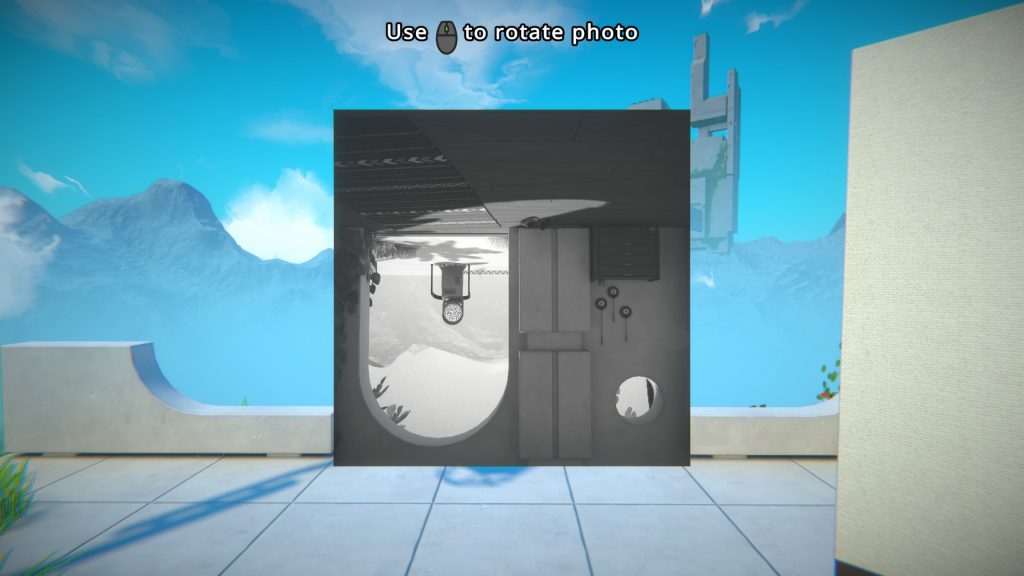

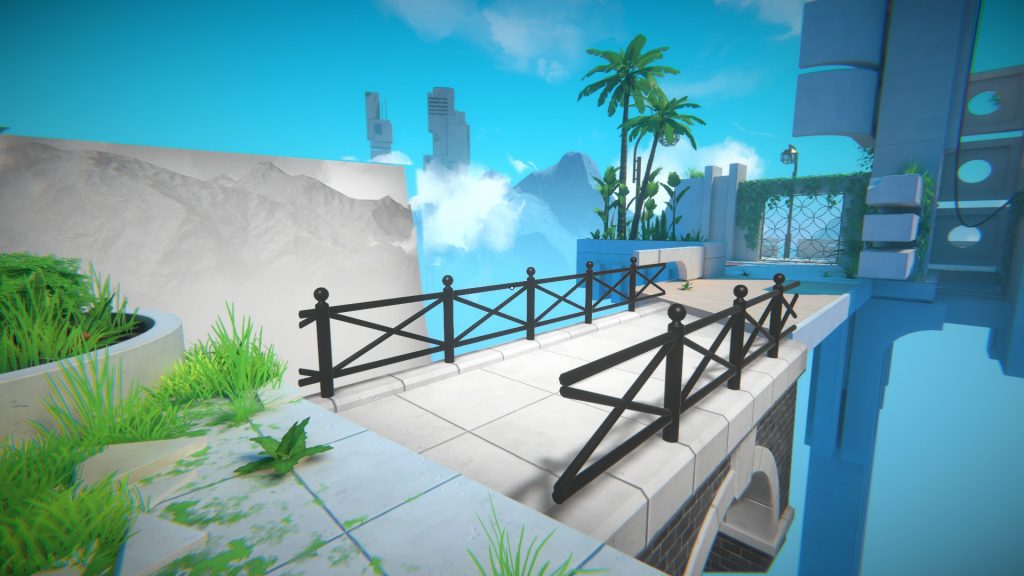

At its core, Viewfinder is the sort of puzzle game I find myself drawn naturally toward, one that introduces a concept that’s simple to understand but deep enough in potential complexity that it invites players to gradually, almost imperceptibly, rewire their brains as they wade deeper. For this game, that captivating central concept is the same one that went up in smoke with F-Stop’s abandonment: the ability to use photographs and illustrations to replicate or otherwise introduce items and scenery into the player’s environment. One recurring example is crossing a yawning gap by taking a photo of a bridge located elsewhere in the gamespace and using that photo to place a facsimile of that bridge where the player can use it to navigate the gap. Photos can be used to replicate key items, create new pathways, and bypass obstacles by overlaying them with images of a distant background.

I don’t know much about programming (my experience with computer code stops at one high school Java class and the intro sections of five different languages on Codecademy) but I assume the tech behind Viewfinder’s photo replication is impressive. Vantage point, perspective, and framing all come into play in requiring the player to think in a way that might be best (and most confusingly) described as simultaneously two- and three-dimensionally.

I’d like to be able to tell you I became a pro at this sort of thinking, that I mastered the sort of perspective-taking and multi-dimensional thought that makes someone good at this game. In truth, it was a lot of trial, error, and luck. We don’t need to talk about the number of times I was sure I had come up with an epiphany-level solution and ended up deleting the path out of the level.

My skill aside, I loved this mechanic and its implementation. Playing Viewfinder repeatedly drew me back to games like Portal that succeed at asking the player to fundamentally rethink their understanding of the three-dimensional space they’d otherwise take for granted.

To the end of introducing players to a simple idea with limitless depth, Viewfinder’s pacing, a make-or-break for complex puzzle games, is mostly solid. New concepts are introduced with inordinately simple puzzles that ensure players understand the way the gameplay is being altered before they’re ushered on to the bigger puzzles where these new concepts shine. I did think the game spent more time than necessary in the pre-camera stage where I was asked to manipulate photos that others had taken or only allowed to take photos with stationary cameras, but maybe that’s just because I had already pre-wired my brain with hype.

I found the difficulty of the puzzles limited, but a lot of that can be chalked up to the pacing and its relative generosity. To each their own, but to me, games like this are less about difficulty and more about realization, about exploring and re-exploring a space until something clicks in the mind that just hadn’t before. Viewfinder had a good few of these moments, some more obvious, but others definitely had me scratching my head until I’d bored deep enough to think outside of it.

These were moments I enjoyed, but a lot of Viewfinder’s potential feels unexplored. Interesting quirks of the camera and its resulting photographs are flirted with and then discarded, and mechanics introduced later in the game to further interfere with our own puzzle navigation serve to whet the appetite more than sate it. This is a theme I felt throughout Viewfinder.

The game’s story, for example, feels underbaked. Its characters all feel potentially interesting, but each claims so little screen time that they feel less like individuals core to the narrative and more historical footnotes, making us stretch to feel how they connect to the present narrative.

Contributing to this feeling of distance is the way the story is told, almost entirely through phone calls and audio recordings. I should clarify that there’s no reason a game can’t succeed in telling a story this way, indeed, Portal 2, the shining city on a hill I’ve chosen to use as a foil for this piece, does much the same and I love it. The trouble here is first in scarcity: Viewfinder has more core characters than Portal 2 and spends far less time with each of them. It’s less that these aren’t deep characters and more that we don’t have time to see the depth that might be there.

But perhaps more than scarcity, a ton of narrative distance comes from where these audio files are spliced in. Only one of the game’s characters, an AI cat named Cait, actively speaks with the player without the player acting first. Cait’s character model is simple, and I always felt a sort of disconnection, like the person I was talking to was booming down from above and not really the cat rhythmically purring in front of me, but the frequency and presence of these communications led me to actually feel the development of a narrative relationship. Cait felt like a character embodying the same space as me, and, had the game given me another hour or two with them, I could have really felt that connection thrive.

The other connections, by contrast, are far weaker. Second to Cait in closeness is the player character’s best friend, a woman helping us in our quest to find something in the simulation we inhabit to help us in the real, climate change-scarred world. Our communications with our friend are limited to phone calls that occur every few levels. These calls do more to illustrate the depth of the simulation as they grow more and more distorted than they do to re-establish any real relationship between friends. By the conclusion, she felt like more of a narrative bookend than the best friend she was meant to be.

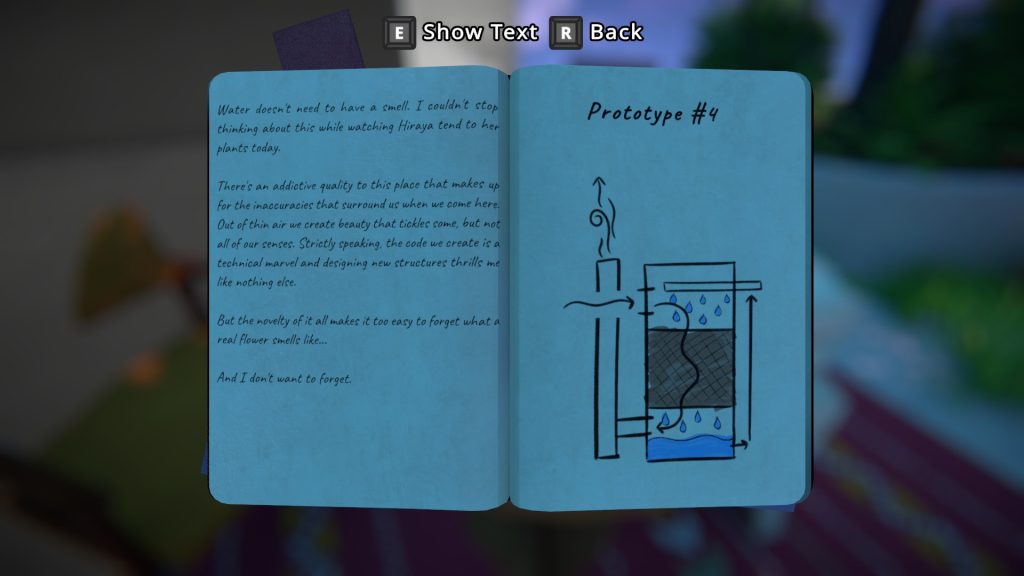

The rest of the characters are similar, made weaker by their distance. Communication from each is limited and often peppered with esoteric jargon beyond our present understanding. Characters spend as much time reminding us that they’re working on a project as they do meaningfully characterizing themselves. Throughout the game and through scattered audio logs we receive glimpses and snippets of their relationships with one another, the ways they work together, the ways they clash, the ways they fight, but never enough to get a three-dimensional understanding of each of them and how they truly connect with one another.

Again, all of this information is piped in through optional audio files. Whether or not their optional nature is a weakness of the game is up to personal taste; I can see an argument for allowing lorehounds their background while leaving space for those who like their puzzles without the extra baggage. But the way the devs have chosen to place these narrative touchstones impacts how I chose to play the game. The gramophones that offer the deep backstory and the telephones that keep us connected to our friend are often placed closely together on the same level, incentivizing us to stay put until one narrative stream is done rather than using the privilege of audio-based storytelling to scope out the level as we listen to the characters speak. This left me playing in a sort of stop-and-go style where I felt I’d either have to stand in one spot until my friend hung up or I’d have to remind myself not to get too far ahead because there’s another gramophone to listen to back near the level’s spawn point.

Further, more than once I ran into a situation where Cait automatically launched into dialogue just after I started the second audio file, leaving me with two simultaneous dialogue streams to keep track of.

The story would have been stronger, I think, if it had chosen a narrative lane and allowed me to focus on one or two background characters at once, leaving the optional audio components until later in levels where they didn’t have to compete for exposure.

Some of my nitpicks with this game come as the result of purposeful developer choice. But more, I think, are probably a matter of time. Viewfinder is a tremendously short game. Online estimates and forum posts peg it at around 2 hours for story completion. I put in at least double that, keeping me outside the Steam refund limit, but only just.

The game introduces some structural ideas, like hub worlds associated with each of the background characters, that clearly seek to tether the game together and create a sort of uniformity of experience, but our experience in each of them is so short that we never really get properly acquainted. I thought it was a fun idea to populate these hub spaces with collectibles found in each of the levels, but again, my time in each space was so short that I never felt motivated to decorate. I found myself wondering how different the game would be if these hubs had been more connected than they are, allowing more regular transport between and potentially even inviting players to use the camera to experiment outside of the levels. That last part might be an unreasonable ask, given the destructive power of the device, but it sure would have been cool.

The idea I’ve been circling around here is the reason I keep coming back to the Portal comparison. Released in 2007, Portal was a short but well-received experimental cult game. It had earned its place in nerd history for sure, but perhaps no more than other standouts of its time.

Portal 2, by contrast, is a masterpiece and one of my favorite games of all time. It takes what Portal introduced and builds on it both narratively and in gameplay, creating a product that is as engaging in both domains. Portal 2 is far longer, more cinematic, and more complete than its predecessor. But it needed that short experimental leap to get there.

I don’t mean to put these layers of expectation on Viewfinder. At the end of the day, Sad Owl may be more than just one guy now, but Portal at its low point of investment still had the full backing of Valve. Still, when I play Viewfinder, I feel the potential I felt in Portal. I found myself over and over again running through this game’s levels and hoping both that this game would find success and that its developers would be interested in a beefier sequel that really investigates the power of its core concept. Maybe Viewfinder isn’t the next Portal, but with an idea like this, its sequel has potential to be whatever its devs want it to be.

Quick Review

Game: Viewfinder

Developer: Sad Owl Studios

Published by: Thunderful Publishing

Available for: Playstation 4, Playstation 5, Windows PC

CONTENT

Microtransactions: None

Tedium: None

Violence: None

Content: Planar existentialism

FEATURES

- Environment manipulation

- Spatial puzzling

WHAT I LIKED

- Photo mechanic – Viewfinder’s central mechanic of duplicating items and spaces with its special camera is one that felt new and intriguing when I was introduced to it and maintained that feeling for the remainder of the experience. This is a game unlike its peers, one that challenges players to think differently.

- Puzzle pacing – Mechanics are introduced slowly and in a way that guarantees core concepts are understood before the player moves on.

- Creative, experimental vibe – The regular gameplay of Viewfinder is interspersed with quirky, fun little one-off elements that serve to make spaces that could otherwise feel same-y or bland feel special. Famous paintings, games, and chalkboards make the space feel a little more lived-in, the way it’s meant to be.

CONCERNS

- Brevity – This is a short game, the average playtime clocking in at around two hours.

- Limited depth – For all the options inherent in its core camera mechanic, Viewfinder mostly plays it safe. A few new mechanics are introduced over the game’s levels, but before long you’ll have seen most of what the game has to offer.

WHO’S IT FOR?

If you have any interest in an experimental puzzle game that invokes the feel and novelty of a game like Portal, Viewfinder might be right up your alley. Conversely, if you’re looking for a longer or more complex experience, or if you hate experimental puzzle games that invoke the feel and novelty of Portal, Viewfinder is probably a terrible place to start.